- Back to the Ecology Plexus Page

Back to The Plexus Home Page

THINKING GLOBALLY ABOUT BIODIVERSITY

ON CHATHAM ISLAND

(OR, WHAT I SAW WHEN I WENT

TO THE CHATHAMS)

11 July 1997

Arrival

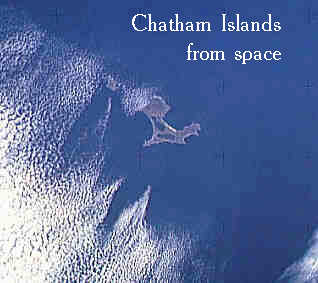

Buffeted by the morning ocean winds, as our Dornier Metro III tilted to

the final approach leg, my first views of Chatham Island surprised me in

two ways.

First, I discovered how much of the island area consists of lagoons and water-edge strand. And second, how much of the land area has been turned to range for domestic livestock.

As part of research for my textbook-writing project on managing viable

wildlife populations, and part personal tour, I was visiting for a short

time to explore the native corners of Chatham Island, to seek out its rare

plants and birds, and to better understand the ecology of this unique Pacific

isle.

A Unique Address

Already I had known that CI is indeed unique in many ways. For one, it is one of the few oceanic islands or archipelagoes that resides between 40 and 50 degrees either north or south latitude. My home near Portland, Oregon, in the United States, is nearly the same latitude as that of CI in the southern hemisphere.If were to travel west from Portland across the north Pacific, I would not encounter an island group until I reached the Kurils of Russia, then Hokkaido and northern Honshu of Japan, and southern Sakhalin of Russia but these are geologically and ecologically utterly unlike the CI group. In the north Atlantic at this same latitude, but traveling east, I would encounter Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and a few small islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but none of these constitute isolated oceanic islands like CI; and then nothing until a few offshore islands in France and Spain.

Even in the southern hemisphere, the CI group is nearly unique. Traveling west from South America into the south Pacific, I would first pass over the Archipelago de los Chonos, an uninhabited group of dozens of rugged islands just off the Chilean coast. And then nothing, until Chatham Island. New Zealand itself offers a few other island groups in this 40-50 degree south latitude zone, including Stewart Island and its neighbors, as well as the tiny uninhabited dots of The Snares, Antipodes Island, and Bounty Island.

Further west at this same latitude, we hit nothing but ocean until the few islands off Tasmania: the inhabited coastal Bruny Island and Maria Island, and several uninhabited tiny islets such De Witt Island and Maatsuyker Island. Now we are in the South Indian Ocean and, traveling again west, encounter only three tiny island groups there: Isles Kerguelen of French claim, which consists of Kerguelen Island (or Desolation Island) and about 300 tiny islets, which has but a science base at Port-Aux-Francais of about 100 inhabitants; Crozet Islands of French claim, which is a rugged, uninhabited archipelago of six islands about 2400 km from Antarctica and is designated as a national conservation area; and the Prince Edward Islands of South African claim, which includes two rocky, rugged, mostly uninhabited islands 1900 km southeast of South Africa. Let us cross into the South Atlantic, and it's a lonely journey there, for we encounter only Gough Island (or Diego Alveraz Island) of U.K. claim, an uninhabited and densely wooded plot of land only 13 km by 6.5 km in size and housing an automated weather station and a wildlife reserve.

So back to Chatham Island, and as we land I realize, in my imaginary global tour, that this is one of the few inhabited oceanic island groups in the world at this general latitude, in either the northern or southern hemisphere.

CI also occurs below the "tropical convergence zone" which is an invisible,

snaking line that here demarcates subantarctic climatic conditions.

The zone actually snakes just south of Stewart Island but north of CI.

This makes CI the only inhabited oceanic island in the world having a subantarctic

(or subarctic) climate and that has originated from an ancient super-continental

land mass (Gondwana) that still houses some of its very ancient and more

recently evolved but unique life forms. These are what I came to

see.

Right: Sperm whale sounding

off the Kaikoura Coast of

South Island, New Zealand.

Photo © Bruce G. Marcot

What Passed Here Before

Many life forms have passed this way before but have vanished forever. The paleontologists Tennyson and Millener reported bird extinctions from adjacent Mangere Island (MI) and that humans have greatly altered MI's natural ecosystem "probably over several hundred years."Polynesians arrived on CI 400-450 years ago and likely visited MI to collect birds or seals. Then Europeans first visited CI in 1791. A report from 1871-98 suggested that MI was at that time covered with "low rigid scrub" native forest. Farming began on MI in 1892 and the island was settled permanently by 1895. Two years later, the native vegetation of MI was burned for farming. During 1868-1900, bird collectors visited MI.

By 1900 came the major change for MI. Sheep, goats, and rabbits were introduced and MI quickly became denuded from grazing and burning. In the early part of the 1900's, cats were introduced to control the rabbits. The cats died out by 1950 but not until they had killed an unknown number of nesting seabirds.

Tennyson and Millener reported fossil bones on MI of 26 bird species.

Up to 22 of these have become extinct on MI, including crested penguin,

two rails, shelduck, fernbird, bellbird, 2 petrels, grey-backed storm-petrel,

Dieffenbach's rail, and kaka. They concluded that "all extinctions

on MI during the last 450 years or so probably resulted from human interference,"

principally hunting, deforestation, and the introduction of cats.

The Old and the New

CI has undergone changes very similar to those on MI. This means that the remaining natural reserves on CI, with their biotic treasures, are all the more important to science and conservation. Over the next few days I would hike the tracks of Hapupu Historic Reserve, Henge Scenic Reserve, Tuku Reserve, and various coastlines and corners of CI.The vegetation of the reserves on CI are indeed global treasures. Nearly 40 plant species are endemic to CI and many appropriately bear the specific epithet "chatamica."

For example, in Henge S.R., I saw the tree called karamu or Coprosma chatamica of the Rubiaceae family This is a mostly tropical and subtropical plant family, but here was this disjunct species, a tree growing up to 15 meters tall with shiny thin leaves and hairy branchlets, in the subantarctic climate and a local endemic to CI. I also saw the Chatham Island matipo or Myrsine chatamica of the Myrsinaceae, another mainly tropical plant family, but here was this disjunct endemic, a 6-8 meter tall shrub or tree with dull green leaves and red hairs on the midrib, growing in hollows and swamp sites. Also present was the endemic Chatham Island mahoe or Melicytus chathamica of the Violaceae family, with lance-shaped, sharply-toothed leaves 5-12 centimeters long, growing as an understory tree to 5 meters tall in rapidly revegetating regions of the coastal reserves. Another reserve plant I saw was the heart-shape leaves of the kawa kawa or Macropiper excelsum of the mainly tropical Piperaceae family, another species on CI disjunct from its mostly tropical heritage.

Other native shrubs or trees I saw in CI reserves include akeake or Dodonaea viscosa of the Sapindaceae family, a small tree to 6 meters with bark reddish-brown, thin, and flaking off in beautiful long narrow strips; the kopi (CI name) or karaka (NZ name) or Corynocarpus laevigatus of the Corynocarpaceae family which has only this one species; and the mahoe or whitey wood, Melicytus ramiflorus, a more widespread relative of the endemic CI mahoe mentioned above.

Tuku Reserve houses the small trees Dracophyllum arboreum of the Epacridaceae family, a small family almost confined to Australia and New Zealand; this entire family is very novel and new to me, and I am delighted to find these trees and sketch them. Other Tuku natives that I found include lancewood or Pseudopanax, probably P. crassifolius, in its early growth form having a unique splay of long narrow leaves, of the family Araliaceae; supplejack or kareao, Ripogonum scandens, with opposite, pointed leaves, of the family Ripogonaceae, which has only 5 species including 4 in Australia and this one in NZ; and hound's tongue fern or Phymatosorus diversifolius of the ancient family Polypodiaceae.

Elsewhere on the island I see stands of kopi trees that have died off from wind storm damage or possum damage. The storm damage looks to me to be similar to some of the o'hia and koa trees killed on Hawaii by Hurricane Iniki that hit the island of Kauai in 1992. Iniki had stripped and killed much of the native, highland tree overstory there. This left an understory comprised of either native shrubs or regenerating native trees in the native vegetation of the highlands, or of lantana and other dense, exotic and noxious weeds in the disturbed vegetation of the lower elevations. I can see how exotic weeds have similarly gained a foothold here on CI in the presence of forests damaged or destroyed by storms or possums.

Left: This is what Chatham Island originally looked like --

tree ferns and other native vegetation. This still exists on the

island but only in tiny isolated reserves. Tuku Reserve, Chatham

Island. Photo © Bruce G. Marcot

Below: This is the landscape of Chatham Island today -- mostly

annual grasses, bracken fern, and gorse, all exotic weeds. Most of the

native forests have given way to a myriad of sheep. Photo ©

Bruce G. Marcot

The Natives and The Newcomers

The bird fauna of CI is a poignant reflection of how the native and the exotic have intermingled here among the surprising array of habitats. In the reserves' native forests and fens of treeferns and Dracophyllum, I spot grey duck, fantail, and the endemic Chatham Island warbler, all of which are found in the less disturbed natural environments. Out among the grazing pastures and weedy shrublands I see welcome swallow, greenfinch, domestic goose, harrier, skylark, pipit, and starling, species that thrive in disturbed environments.I tape bird songs in the dense bush tracks of the reserves, and later compare them to known recordings to reveal the presence of several non-native, exotic species even in the reserve forests: song thrush, hedge sparrow, greenfinch, silvereye, and cuckoo. I worry that such exotics in the native tracts are unduly competing for resources with the scarcer native birds.

Actually, silvereye, along with welcome swallow and spur-winged plover (called Australian lapwing elsewhere), are birds that have self-invaded NZ and CI by following the "roaring forties" from Australia; several colonizers of each species made it across the long oceanic stretch beginning in the mid-1800's, and spread out from there to eventually colonize virtually all of NZ. CI was only another stop along their push eastward. But the thrush, sparrow, and finch were deliberate introductions of exotic species by exotic people, ostensibly to bring in a bit of "home" to this otherwise foreign land. Unfortunately, many of the introduced birds have indeed outcompeted the natives, and some, such as the cuckoos, actually lay their eggs in nests of native bird species for them to take over the tasks of chick-rearing.

And of course the omnipresent possum has its analogue throughout the Pacific Islands in the form of the mongoose, introduced to so many archipelagoes. Both species have wreaked ecological havoc on ground-nesting birds throughout the Pacific.

For example, the mongoose was introduced to Fiji from Hawaii in 1873 to rid the islands of introduced rats. But mongooses are diurnal (active during the daytime) and the rats are nocturnal (nighttime), so the mongoose did not compete with the rats but simply added to the decline of the native ground-nesting birds. On Fiji, the mongoose proceeded to exterminate some 7 native bird species including the purple swamp-hen and the banded rail; on Hawaii it likely exterminated similar ground-dwelling species.

On CI and NZ, the possum is causing similar havoc with the native, ground-dwelling and especially the flightless or more docile species. Early in history, possums were likely introduced as food to the Bismarck Archipelago and since have caused similar ecological problems there. CI's ecology is unique, but its ecological problems are not.

The rocky coastlines and offshore stacks such as Sisters house an amazing variety of largely native shorebirds and sealife, more diverse than I have seen anywhere else outside New Zealand. Along the steep sea cliffs of Matarakau, I spot giant petrel and the docile, endemic Chatham Island shag and Pitt Island shag, and then the brief, sleek black hump of a Minke whale.

Further along, I encounter the wonderful, talkative, and very rare, endemic Chatham Island oystercatcher at a 2-egg nest site -- being well studied by CI's own wildlife biologist, Frances Schmechel; and the skittish black shag, never allowing a close approach.

Based

on origin, there are perhaps two main classes of birds on the Chatham Islands

group: natives and introduced.

Based

on origin, there are perhaps two main classes of birds on the Chatham Islands

group: natives and introduced.

The native birds can be split into four other classes:

The introduced species can be split into two additional groups:

In this classification, the weka is unique in being native and endemic

to NZ but introduced to CI (for hunting sport) and, like some of the exotic

introduced species, causing ecological damage particularly to native ground-dwelling

birds.

It is a brief and somewhat biased sample, but in my short ecological tour of CI, two-thirds of the 24 bird species I saw are native and one-third are introduced, but this includes seabirds as well as terrestrial (that is, forest and open-country) birds. When you factor out the largely native seabirds, the story is quite different. Of only the terrestrial birds, three-quarters of those I encountered are introduced and only one quarter are native. And of the introduced terrestrial birds, 60 percent are exotics introduced by humans. Clearly, the terrestrial quarters are being overrun by nonnative immigrants.

Chatham Island Oystercatchers,

a native species endemic only to

the

Chatham Island group.

© Bruce G. Marcot

Let's return for a moment to one of the native species groups.

Why are the "phenotypic difference" species (group 3) of interest?

Scientifically, like the endemic subspecies (group 2), they may be a hallmark

of evolution to come; given time and continued genetic isolation, they

may eventually evolve into unique subspecies or perhaps even species, as

cases of "natural evolutionary experiments" so to speak. Such ecological

divergence has its extremes in isolated oceanic island systems like the

Chathams and has resulted in the amazing adaptive radiation of the Hawaiian

honeycreepers and Darwin's finches on the Galapagos Islands. Given

time, isolation, and lack of ecological disturbance, CI might have evolved

(and might yet evolve) more of its own unique "flying laboratories."

Chatham Island Pigeon, an endemic subspecies

of the New Zealand

Pigeon. Like the other

native endemic wildlife species of Chatham

Island,

this is found more frequently in the forest reserves

on the island.

© Bruce G. Marcot

That is why it is critical to protect much of what is left; not just

for the current, unique global contribution to biodiversity, but also for

providing conditions to maintain long-term evolutionary processes.

On CI, Hawaii, and the Galapagos, nature is dynamic, and threatened reserves

are only one step in its long-term survival.

The Time Machines

Hiking the reserves of CI is like hiking few other places on Earth, but it did seem redolent of the high-elevation native bush forests of Maui, the Big Island of Hawaii, and Kauai. In the Hawaiian islands, many of the native birds are becoming equally as rare as the taiko and black robin of the Chathams, and even the more common native species of Hawaii are becoming increasingly scarce and skittish (except for the scolding, flocking fantail on CI, which too has its analogue in Hawaii as the 'elepaio flycatcher). But one major difference here on CI is the remarkable diversity of sea birds, which are strikingly reduced on the mid-oceanic Hawaiian chain.I love the reserves of CI -- of course, given the people of the island, the entire CI cannot and probably should not become a reserve -- but those few reserves are like islands within islands, and stepping into them is like stepping into time machines to the distant primordial past. They give a taste of what these once-extensive forests might have been like, with the tree silhouettes of Cyathea (tree ferns), kopi, and Dracophyllum, occurring in ancient environments only until recently dominated extensively across CI by karamu, Chatham Island matipo, Chatham Island mahoe, and others. This is a remarkably diverse flora with many endemics, particularly diverse for so low-lying and remote an island below the Tropical Convergence Zone.

Chatham Island Shag,

another endemic species of

Chatham Island.

© Bruce G. Marcot

But now my heart sinks when I return to the present CI and walk its

landscapes and crash through mostly bracken and gorse.

Of Mites and Men

And yes, much of the native habitat of CI has been greatly altered for sheep ranching. I hadn't seen so much gorse since I hiked the slopes above 2000 meters on the south face of Mauna Kea of Hawaii. There, the native vegetation too had been cleared for short-lived farming and ranching, until it became clear that the domestic sheep, mouflon, and cattle were quickly destroying native plants and habitats used by the vanishing native bird fauna of highland Hawaii.The State of Hawaii has since engaged in an eradication program by allowing the hunting of both sheep and cattle(!). They also have engaged in the terribly expensive and labor-intensive task of fencing in some of the major reserves, such as the largely closed Hakalau Reserve on northeast Mauna Kea, which I have also visited. Thanks to these efforts, Hakalau Reserve is slowly being revegetated with native trees, and down wood there is playing an important "nurse tree" role for tree regeneration, but much of the upper elevation forests of the Reserve may have been irreparably lost.

Like Hakalau and other Hawaiian reserves, fencing out livestock from the reserves of CI is a necessary expense to help maintain or restore the native vegetation there as well.

The State of Hawaii also has begun a program on Mauna Kea of introducing the red spider- mite, a tiny red dot of an exotic arthropod species that lives in dense webbing and feeds on the seeds of gorse. Laboratory tests assure that the mite feeds only on gorse, and have shown that it eats up to 95 percent of all gorse seeds from individual plants (Paul Snowcroft, pers. comm.). But that last 5 percent might be just enough to keep the gorse invasion healthy.

And here I stand on CI, with oceans of gorse and seas of bracken, with

nary a mite in sight.

Departure and the Future

As the azure pools of Chatham Island slip below me in a white haze, I think

of the lessons I have learned here. I am truly amazed at how so isolated

and distant an island can host such an amazing density of sheep and their

amazingly widespread ecological damage. This only highlights how

special are the reserves of CI and its island neighbors, and how important

are the efforts needed to fence or trap out the worst of the invaders.

Can the reserves persist indefinitely? Is this a landscape in long-term ecological balance? I can't see that from here, although I am viewing but a snapshot during my short visit. But lessons from other Pacific Islands have already long since raised the warning flag. I hope that achieving a long-term ecological balance is part of the islanders' interests; it is certainly to their long-term advantage.

I wonder what I will see when I, or the next generation of field ecologists,

visit here next.

Addendum and AcknowledgmentsMy gratitude to reader Maui Solomon, grandson of Tame Horomona Rehe (Tommy Solomon) who is reputed to be the last full-blooded Moriori, for correcting a previous error I made in this essay, in which I implied that the Moriori have vanished. Mr. Solomon noted that there still are several thousand people of Moriori descent who identify as Moriori on the island, and he suggested a visit to their website www.moriori.co.nz. Mr. Solomon is General Manager of Hokotehi Moriori Trust, which "...is the organisation representing Moriori people everywhere, [and which] is committed to helping to regenerate the ecology of the islands and have recently established our own nursery at Henga to assist with this task." To that, I owe Mr. Solomon thanks and gratitude for caring for future generations to come.

My thanks also to Dr. Frances Schmechel for hosting me and my travel colleagues during our visit to the Chathams. May her research on the endangered Chatham Island oystercatcher, and her difficult work on the remote Bounty Islands and other distant corners, help promote the conservation actions they deserve.