Titan on Earth

All terrestrial photos taken by and © Bruce G. Marcot.

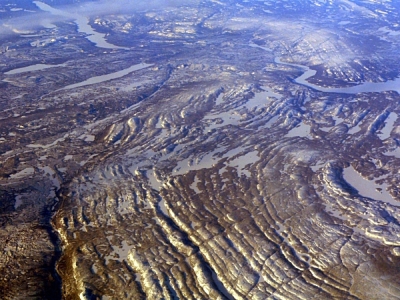

Once upon a time, during a long, mid-winter international

flight, I found myself over the immense and amazing Laurentian Plateau of

eastern Canada. As related in one of my Ecology

Picture of the Week

episodes, this vast landscape -- also called the Canadian Shield -- is a

land of ancient bedrock scraped raw by the last sweep of continental glaciers

that covered most of northern North America.

With immense pressure, the glaciers flattened the ground and scooped out depressions that, as the ice melted and retreated, filled with meltwater. Today we see them as lakes -- now white and frozen in the winter cold.

It

struck me how visually similar this landscape appeared to the lakes of methane

on Titan, the largest of Saturn's moons, as imaged by NASA's Huygens probe

orbiting Cassini spacecraft in

January 2005, when compensating for the visual appearance, using radar

imaging to pierce Titan's dense atmospheric haze.

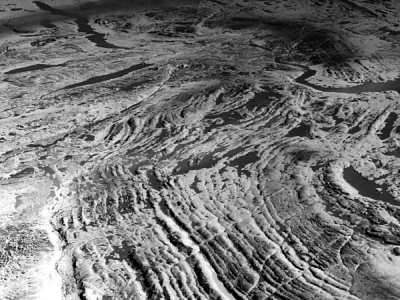

First, here are photos I took of the Canadian Shield in natural color and then converted to grayscale, reversed, and contrast-enhanced:

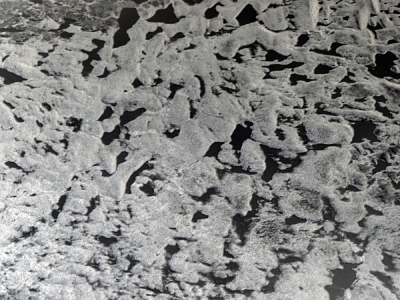

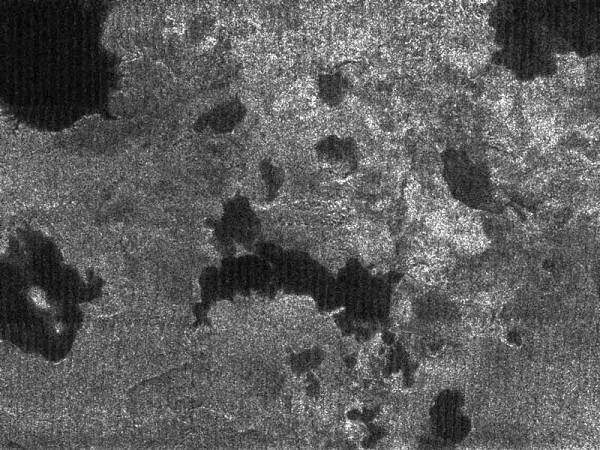

Now compare the above converted images on the right side, to

those taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft of the landscape and methane lakes of

Titan:

Of course, we are viewing a completely different geology on Titan, and I don't want this to be merely a visual trick of manipulating images ... but it is striking to me how the methane lake landscapes of Titan do resemble the geography and orography of the glacially-carved landscapes of the Canadian Shield. It has me wondering if Titan had, at one time, also experienced some form of continental glaciation of its own, perhaps glaciers made of methane?

- - - - - - - -

Update: I appreciate the response to the above from astronomer Brad Smith, who noted that the images from Titan were created from scans of radar reflectivity fo the surface by the orbiting Cassini spacecraft, not by the Huygens lander as I initially noted (and have now corrected in the above text). Smith also noted that the liquid hydrocarbons -- mostly methane and ethane -- that compose the lakes have far lower reflectivity than the surrounding landscape, and thus appear darker. Smith noted that we do not yet have any explanation for what created the lakes, but surmises that they may merely be topographically low areas into which liquid hydrocarbon streams flow. (Of course, that they might be topographically low areas, and especially how those low areas were initially created, is the point of my text, above.)